Meningitis complications and prognosis

Up to 28% of patients with bacterial meningitis suffer complications during or after its course. A wide range of neurological problems may occur, ranging from focal neurological deficits, to seizures, cognitive impairment or hearing loss. Complications may present at any time, though the majority of these complications occur early in the course of the disease. At discharge, roughly 10% of patients have neurological complications. In those who recover, up to 20% experience long term neurological complications.

Risk factors

Different clinical features at baseline have been used to estimate individual risk of complications in patients suffering bacterial meningitis. An altered mental status upon presentation, hypotension, and seizures are all associated with adverse outcome (meaning death or neurological deficit at discharge). Subsequently, a delay in initial antibiotic treatment is associated with worsening of these clinical features.

Aside from these clinical risk factors, the rate of complications is greatest in patients with pneumococcal meningitis. One suggested explanation for this is the fact that debris from these killed bacteria may stay biologically active and stimulate a host inflammatory response leading to tissue damage.

Complications

Complications may be sudden or gradual in onset and can appear at any time after the onset of symptoms, including after the completion of therapy. Although many neurologic complications are severe, others, such as hearing loss, may be subtle or inapparent during the early phases of infection. The following complications are common:

Increased intracranial pressure (ICP)

Increased ICP is primarily due to cerebral edema, caused by vasogenic, interstitial, or cytotoxic mechanisms. Mild increases in ICP cause headaches, confusion, irritability, and nausea/vomiting. Severe increases in pressure may lead to bradycardia, altered mental status, papilledema leading to loss of vision )(up to 9% of adults), cranial nerve palsy (N.VI), and lethal herniation of cerebellar tonsils.

Seizures

Roughly 15-30% of patients with bacterial meningitis suffer seizures. In 5% of patients seizures are present at presentation, up to 15% may develop seizures during the course of the disease. Early onset seizures are more common in patients with a history of alcoholism.

Seizures during an episode of acute meningitis are often a poor prognostic sign in adults. In a series of 696 patients with community-acquired bacterial meningitis, seizures were associated with a higher risk of neurologic deficits at hospital discharge (24 versus 6%) and death (41 versus 16%). All five patients with status epilepticus in this case series died. Patients experiencing seizures during the course of a bacterial meningitis have an increased risk of recurrent seizures the following years compared to initially seizure-free patients.

Focal neurological deficits

Focal neurologic deficits are common complications of meningitis, with an incidence ranging from 20 to 50%. The deficits include cranial nerve palsy, monoparesis, hemiparesis, gaze preference, visual field defects, aphasia, and ataxia, and most are present on admission. As with other neurologic complications, the rate of focal deficits is significantly higher in adults with pneumococcal meningitis compared with other pathogens. Focal neurologic deficits may be present at discharge in 65% of those with pneumococcal versus 33% with meningococcal meningitis. Most focal deficits resolve with successful treatment of the meningitis, but long-term disability can occur.

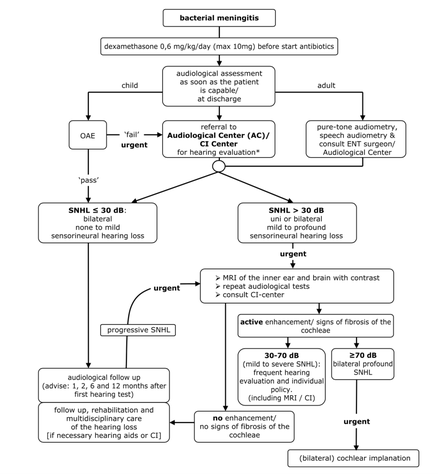

Hearing loss

5-35% of patients will develop permanent sensorineural hearing loss, and profound bilateral hearing loss occurs in 4% of patients. Not all hearing loss after meningitis is permanent. Transient hearing loss is usually secondary to a conductive disturbance, whereas permanent hearing loss can result from damage to the eighth cranial nerve, cochlea, or labyrinth induced by direct bacterial invasion and/or the inflammatory response elicited by the infection.

Cochlear implantation is the method of rehabilitation in profound and complete hearing loss. In postmeningitic patients with a cochlear implant, the results are usually fairly good. However, it is of extreme importance to have a patent cochlear lumen to insert the complete cochlear electrode array to obtain the best results. Meningitis can cause an immune reaction within the cochlea leading to fibrosis and finally to calcification of the cochlear turns (labyrinthitis ossificans), which makes implantation extremely difficult or even impossible. Hearing of postmeningitic patients should be evaluated as soon as possible and followed up frequently.

Cognitive impairment

Neuropsychological impairment is common in survivors of bacterial meningitis. A meta-analysis of three trials including 155 adult survivors of bacterial meningitis found that cognitive impairment occurred in 32% of patients. The meta-analysis found no difference in cognitive impairment between survivors of pneumococcal and meningococcal meningitis, although two of the studies included found worse cognitive outcomes in patients with pneumococcal disease. Dexamethasone does not appear to alter the incidence of cognitive impairment.

Cerebrovascular complications

Bacterial meningitis may lead to vascular complications such as thrombosis (for example of dural venous sinuses), vasculitis, acute cerebral hemorrhage, and the formation of mycotic aneurysms in small, medium, and large cerebral vessels. There are reports of patients developing cerebral thrombosis affecting the brainstem and/or thalamus as a subacute complication of pneumococcal meningitis 7 to 19 days after initial presentation.

A number of other rare cerebrovascular complications have been described in isolated reports. These include hemorrhagic stroke and thrombotic infarction an/or subarachnoid hemorrhage into the brainstem.

Unusual complications

A variety of other neurologic complications rarely occur in adults with bacterial meningitis:

- Extra-axial fluid collections that are infected (subdural empyemas) or sterile (subdural effusions or hygromas). Drainage is mandatory if subdural empyema develops. Detecting subdural empyemas and distinguishing them from sterile fluid collections requires correlation between clinical and imaging findings.

- Spinal cord complications such as transverse myelitis or infarction, presumably as a direct result of local vascular changes with secondary cord ischemia.

- Brain abscesses and focal cerebritis may be causes of or complications of meningitis. When they are complications of meningitis, they occur with higher frequency in patients infected with certain uncommon causes of meningitis such as Enterobacter or Citrobacter spp and tend to occur in the frontal or temporal lobes at the grey-white matter junction.

- Aneurysm formation of focal intracranial vessels, presumably secondary to inflammatory changes in the blood vessel wall.

- Ventriculitis, which may manifest as ependymal thickening and enhancement, generalized or segmental ventricular dilatation, and debris in the dependent portions of the ventricles by CT or magnetic resonance imaging.