Diagnostics in meningitis

Although the annual incidence of bacterial meningitis is declining, it remains a medical emergency with a potential for high morbidity and mortality. Clinical signs and symptoms are unreliable in distinguishing bacterial meningitis from the more common forms of aseptic meningitis; therefore, a lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid analysis is recommended. Empiric antimicrobial therapy based on age and risk factors must be started promptly in patients with bacterial meningitis. Empiric therapy should not be delayed, even if a lumbar puncture cannot be performed because results of a

computed tomography scan are pending or because the patient is awaiting transfer.

Neurological examination

Examination for nuchal rigidity:

Nuchal rigidity may lead to the inability to touch the chin to the chest and is can be demonstrated by active or passive flexion of the neck. Several tests exist to assess meningismus in patients suspected of (bacterial) meningitis such as Brudzinski’s and Kernig’s sign.

- Brudzinski sign refers to spontaneous flexion of the hips during attempted passive flexion of the neck

- Kernig sign refers to the inability or reluctance to allow full extension of the knee when the hip is flexed 90 degrees. The Kernig test is usually performed in the supine position, but it can be tested in the seated patient.

Although nuchal rigidity and Kernig and Brudzinski signs were described over a century ago, their accuracy was not assessed in a large, well-designed prospective study until a 2002 report of 297 patients with suspected meningitis. When meningitis was defined as ≥6 white cells/microL of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the sensitivity was extremely low (5 percent for each sign and 30 percent for nuchal rigidity); the specificity was 95 percent for each sign and 68 percent for nuchal rigidity.

Neither Kernig nor Brudzinski signs performed much better among the 29 patients with moderate meningeal inflammation or the four patients with severe meningeal inflammation, defined as ≥100 and ≥1000 white cells/microL, respectively. Nuchal rigidity was present in all four patients with severe

meningeal inflammation but had a specificity of only 70 percent.

Laboratory results

Routine blood results often show an elevated white blood cell count with a shift towards immature forms. In severe disease, patients may have leucopenia. Leukopenia and thrombocytopenia have correlated with a poor outcome in patients with bacterial meningitis. Coagulation studies may be

consistent with disseminated intravascular coagulation. Hypo- or hypernatremia may be present in up to one third of patients but is usually mild.

Blood cultures

Two sets of blood cultures should be obtained from all patients before initiating antimicrobial therapy. Between 50 and 90 percent of patients suffering from bacterial meningitis have positive blood cultures. Blood cultures are positive significantly less often when antimicrobial therapy

has been given before obtaining samples.

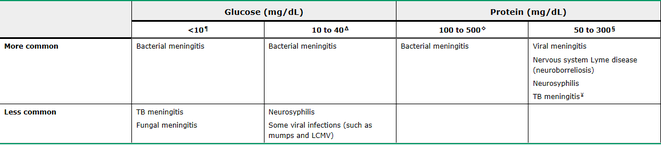

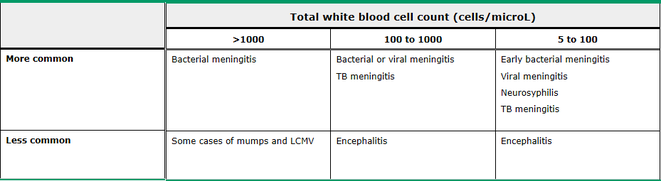

Testing of cerebrospinal fluid

Examining cerebrospinal fluid is of paramount importance in the diagnosis of bacterial meningitis, showing increased white blood cell count and sometimes low glucose levels. White blood cell count in viral meningitis typically is up to several hundreds cells/microL, whereas bacterial infections tend to

show thousands. Every patient suspected of meningitis should have cerebrospinal fluid obtained unless lumbar puncture is contra-indicated.

It is not uncommon for LP to be delayed while a computed tomographic (CT) scan is performed to exclude a mass lesion or increased intracranial pressure; these abnormalities might rarely lead to cerebral herniation during removal of large amounts of CSF, and cerebral herniation could have devastating consequences. However, a screening CT scan is not necessary in the majority of patients.

a CT scan of the head before LP should be performed in adult patients with suspected

bacterial meningitis who have one or more of the following risk factors:

- Immunocompromised state (eg, HIV infection, immunosuppressive therapy, solid organ or

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation)

- A history of CNS disease (tumor, mass lesions, focal infection)

- Seizures

- Decreased level of consciousness

- Focal neurological deficitis

- Papilledema

Anyone presenting with suspected meningitis and any one of these risk factors should undergo CT scanning to exclude mass lesions or other causes of increased intracranial pressure. A normal CT scan does not always mean that performance of an LP is safe and that certain clinical signs of impending herniation (ie, deteriorating level of consciousness, particularly a Glasgow coma scale <11; brainstem signs including pupillary changes, posturing, or irregular respirations; or a very recent seizure) may be predictive of patients in whom an LP should be delayed.

When lumbar puncture is delayed, empiric anti-microbial therapy should be initiated as soon as blood cultures have been taken, as well as dexamethason 0.15mg/kg (or 10mg) every 6 hours and anti-viral therapy with intravenous aciclovir when HSV infection is suspected.

A Gram stain should be obtained from cerebrospinal fluid when bacterial meningitis is suspected since it has the advantage of suggesting the bacterial etiology roughly one day or more before culture results are available. Different Gram stains are associated with different pathogens:

Gram positive diplococci => pneumococcal infection

Gram negative diplococci => meningococcal infection

Small pleopmorhic Gram negative coccobacilli => haemophilus influenzae infection

Gram positive rods and coccobacilli => listerial infection

The reported sensitivity of Gram stain for bacterial meningitis has varied from 60 to 90 percent; however, specificity approaches 100 percent.